Editorial note: I originally wrote this piece at my primary blog, long ago. I thought I had crossposted it here, as it has a number of both philosophical and religious issues.

I realized I hadn't, when looking for it to link to a pending blog post that will be up in about 10 days. So, here it is, with light edits.

===

I recently wrote an essay for The Electric Agora, an online philosophy and social sciences magazine headed by Dan Kaufman, about parallels between Constitutional originalism and religious, especially Christian, fundamentalism.

On second request for rewriting, in part to get shorter length and tighter focus they wanted, and in part because they didn't see it as an actual parallel, I think, I whacked out what I wrote about parallels in supersessionism, and further cuts were made after that. But, I thought that was cutting some meat, so I gave the OK to Dan while knowing I could run my own version here.

Christian supersessionism, of course, is the idea that Judaism is a "lesser" religion in some way, shape, or form, as Christianity has now fulfilled it, or superseded it. And, on the textual side, the New Testament has fulfilled the prophecies and superseded the mandates of the Old Testament.

I do think a similar parallel exists, namely in the relationship between the Constitution (New Testament) and the sometimes overly-maligned Articles of Confederation (Old Testament).

And, because I think this "follows," I am running the whacked part of that essay here.

Beyond that, Joseph Ellis is wrong about the metaphysics behind the Articles of Confederation.

That leads to another parallel between types of fundamentalisms, or originalisms. Where more than one sacred text is involved, how do they relate to one another?

Dan Kaufman has written about Christian supersessionism, which is in part based on the issue of relations of some texts to others.

Rather than seeing the New Testament as one possibility for an organic evolution from the Tanakh/Old Testament, it supersedes it. Here again, we have a parallel.

This one partially involves the Declaration of Independence, but also takes in the first governing document of America’s original 13 United States.

The parallel is clear. Rather than seeing the Constitution as one possibility for an organic evolution from the Articles of Confederation, it supersedes it, under Constitutional fundamentalism.

For that, too, we have to start with the Declaration of Independence,

per its text.

First, the Declaration starts:

The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen united States of America,

When in the Course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands... (14)

All of that indicates that the Declaration's authors and ratifiers saw themselves as representing one nation. An inchoate and loosely connected one, yes, but one nation.

The last paragraph refers again to "united States of America." Again, loosely connected, perhaps, but one nation.

Ellis talks elsewhere about Jefferson and Adams as ambassadors. He ignores that they were ambassadors of the "united States of America, in General Congress, assembled," and not of Virginia, Massachusetts, etc.

Indeed, I can make half an argument that the Articles of Confederation were half a step backward from this.

So, what’s at stake in all of this?

This ultimately is more than an academic discussion of Constitutional interpretation. Rather, it’s a mindset that affects other aspects of American political philosophy — and larger American political science.

Religious and Constitutional fundamentalism have definite parallels. And, while not all Constitutional fundamentalists are Christian ones (including traditionalist Catholics here), or vice versa, many are. And, in the likes of Rowan County (Kentucky) Clerk Kim Davis, we can even see them intertwine. And, not just at the level of federal courts vs. state officials. State agencies, to take this back to Constitutional fundamentalism, like Texas’ State Board of Education in its choice of history textbooks for the state’s schools, are driven by both types of fundamentalism.

Fundamentalism, per what I noted about “Type 2 heresies,” heresies toward people, although also possible in “Type 1 heresies,” also involves hagiography. It’s hagiography that lies behind American exceptionalism.

These issues are also non-academic outside of the United States. With the end of the Cold War, the fall of the Soviet Union and other geopolitical changes that have opened more countries of the world to considering democratic institutions, the full background of the version of democratic institutions the United States has to offer must be considered.

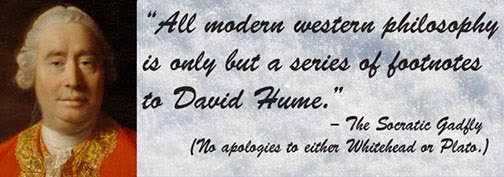

Here Hume, in his thoughts on the British constitution in his opus, “The History of England,” is not fully right. Even the most revolutionary-seeming changes in government have at least a pinch of the evolutionary about them. And, interpreting governments, their texts, and their history in an evolutionary fashion is one antidote against fundamentalist, or originalist, mistakes.

The third main issue, or strategic move, of Ellis is to essentially dismiss the whole mindset behind Lincoln's "fourscore and seven years" at Gettysburg, rather than noting that that was a deliberate stake in the ground — an assertion that, contra Ellis, the United States did begin in 1776. This let Lincoln reframe the issue of slavery.

It also, although Lincoln did not go as far as a William Lloyd Garrison, let him at least obliquely criticize Constitutional fundamentalism. As I noted, as embodied by people such as Chief Justice Taney, Constitutional fundamentalism was indeed around at this time.

==

I'm now going to drop in the full amount of a related blog post from 2010 from over there.

The Economist is

spot on: When people like the Tea Partiers (or Supreme Court INJustice Antonin Scalia) treat the Constitution like conservative Christians do the Bible, looking to it as both infallible and timeless, this is what happens:

When history is turned into scripture and men into deities, truth is the victim. The framers were giants, visionaries and polymaths. But they were also aristocrats, creatures of their time fearful of what they considered the excessive democracy taking hold in the states in the 1780s. They did not believe that poor men, or any women, let alone slaves, should have the vote. Many of their decisions, such as giving every state two senators regardless of population, were the product not of Olympian sagacity but of grubby power-struggles and compromises—exactly the sort of backroom dealmaking, in fact, in which today’s Congress excels and which is now so much out of favour with the tea-partiers.

With Nino Scalia, I think it's a product of his Catholic background, where priests need to interpret Scriptures in light of church tradition. So, St. Nino of Numbnuttery thinks he needs to interpret the Constitution in light of originalism.

And, it's not just Nino, but other intellectuals of the right:

Conservative think-tanks have the same dream of return to a prelapsarian innocence.

There is no such thing; governance, like Hobbes' state of nature, never was primeval.